College for All? Then Create Better Pathways for Low-Income Adults

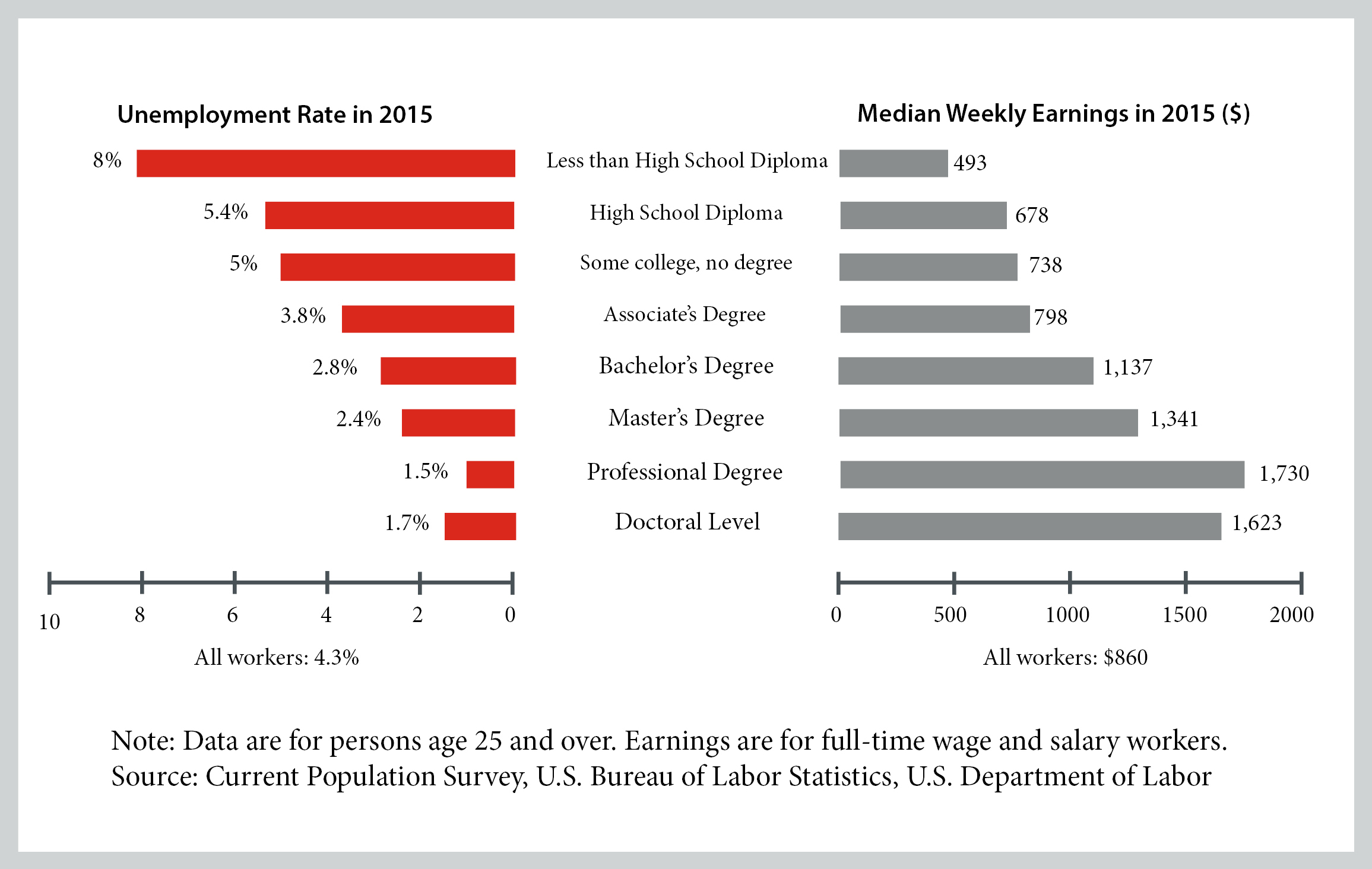

This month, more than three million college students across the nation will heave a sigh of relief and celebrate having gotten to graduation day. They know their chances of getting a job and earning at least a middle-class living are much better with a college credential than without one, as recent Bureau of Labor Statistics data show (see Figure 1, below).

Many low-income adults, though, find the road to a college credential is long and full of obstacles. Career pathways offer a promising solution; Abt research is filling in knowledge gaps on whether that promise can become a reality.

Significant Challenges to Graduation

Cost poses one of the largest barriers to low-income adults entering and completing college. Even at supposedly affordable community colleges, average unmet financial need—the gap between college costs and financial aid awarded plus the student contribution—among students age 24 and older runs annually to $7,734 for full-time students and $3,559 for part-time ones. Lack of time presents another major hurdle. Low-income adult students typically work far more hours than research suggests is optimal for college success, in part because of inadequate financial aid. For the one in four community college students who are parents—most of whom are single parents—they face an even worse time crunch because they juggle parenting responsibilities along with those of work and school.

As a result, the majority of low-income adult students attend college part-time, which lengthens their time to earn a degree and puts them at greater risk for dropping out. Beyond cost and time pressures, low-income adults are more likely to be academically underprepared, causing them to be disproportionately placed in remedial math, reading, writing or English language courses that have high attrition rates, and make it less likely that they persist and complete.

Aside from these general obstacles, another factor in whether low-income adults earn college credentials and whether those credentials translate into higher employment and earnings is that they are more likely than other students to start out in postsecondary certificate programs, rather than degree programs. Short-term certificate programs have grown rapidly in recent years and can be especially attractive to students who need to find jobs or move up to better ones quickly. These programs provide an important entry point into postsecondary education for historically underrepresented students, some of whom lack the academic skills, time, or confidence to enroll in longer degree programs.

While students complete certificate programs at higher rates than degree programs, research is mixed on their economic value. Long-term certificate programs, particularly in nursing, are consistently associated with a substantial earnings payoff. Both short and long-term certificate programs appear to increase employment. Many short-term certificates also appear to increase earnings, though much more modestly than long-term ones. However, the payoff to certificates, whether short or long term, seems to vary greatly depending on the occupational field, the certificate’s alignment with labor market needs, and the program’s alignment with a career path. And many certificate programs are noncredit, meaning that students in them are not earning college credit that would apply toward earning an associate or bachelor degree should they choose to continue on in postsecondary education.

For all these reasons, the career pathways framework holds particular promise for increasing postsecondary attainment and earnings among low-income adults by addressing issues that affect them. Career pathways combine a series of connected education and training strategies with support services and financial assistance to help people secure industry-relevant certification, get a job within an occupational area, and advance to higher levels of future education and employment in that area.

Assessing the Evidence to a Career Pathways Approach

Career pathways offer entry-level training, such as short-term certificates, but in theory enable students to keep moving up to higher-level college programs over time. Ideally, pathway certificates and degrees are closely connected to employer needs in a particular industry, thereby ensuring that educational progress is matched by increased employment and earnings. Twelve federal agencies recently issued a joint letter affirming their commitment to the career pathways framework, including ongoing efforts to incorporate it into policy and funding, and resources to help states and localities build career pathway systems. This framework is also woven throughout the new federal workforce law, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act.

Yet little hard evidence exists as to whether the career pathways framework can deliver on its potential benefits. Abt Global is working to fill that gap with several evaluations of pathway efforts, including the Health Profession Opportunity Grants (HPOG) and the Pathways for Advancing Careers and Education (PACE) initiative. Abt is also evaluating the second round of HPOG grants and the American Apprenticeship Initiative—apprenticeship being one of the oldest pathway models—as well as assessing research and practice on health care and early care and education career pathways in order to design evaluations of them.

Findings about the impact of HPOG and PACE are expected beginning in late 2016 and continuing through 2017. But recent reports offer early insights into how career pathway programs are being implemented, outcomes for participants, their motivations for enrolling, challenges, and program supports. The HPOG Descriptive Implementation and Outcome Study Report found that:

- Participants are predominately low-income single mothers.

- A high percentage (70%) enrolled in and completed training in the first 18 months, while another 14% were still enrolled in the training.

- Two years after entering HPOG, nearly 70 percent of participants were employed, an increase from about half initially. Participants who had completed at least one training were about 10 percent more likely to be employed than those who had dropped out.

- For those who had completed training and were working, average quarterly earnings were $3,942 following training completion, increasing to $5,357 two years after entering HPOG. Among completers, average hourly wages were higher for those in health care ($12.42) than for those working in other sectors ($9.98). Those who completed training in health care jobs were almost four times as likely to have employer-provided health insurance as those in non-healthcare jobs.

Three recent briefs explore career pathway participant perspectives, based on interviews with PACE students. In the brief “Nothing Can Stop Me Now,” participants talk about their motivations for joining the program such as providing financially for their children, serving as role models, and transforming their lives by overcoming significant personal challenges. One participant described it powerfully:

“Since I’ve gone through all this domestic violence, as I was overcoming it, I’ve always been working very hard. I want a better life for my family and my daughter and I. I don’t want my daughter—I want my daughter to look at me and be proud of me and say, ‘Nobody should be treated the way you were treated.’ It’s not acceptable. I don’t want her to ever think it’s acceptable. I want to set an example for her and for her to go to college, to become independent, and to be a strong, confident, independent woman. That’s what I want her to be. That’s what I want to portray.”

These stories underscore the vital importance of finding effective ways – including through career pathways – to help low-income adults enter and succeed in college.